Trust in AI care robots must be rethought

A common criticism of SCRs is that they risk diminishing the human dimension of care, leading to loneliness, objectification, or even deception—especially among vulnerable populations such as the elderly or cognitively impaired. This criticism often stems from what the authors identify as two misconceptions: first, that only the properties of the robot matter in determining trust, and second, that all care contexts inherently require personal trust.

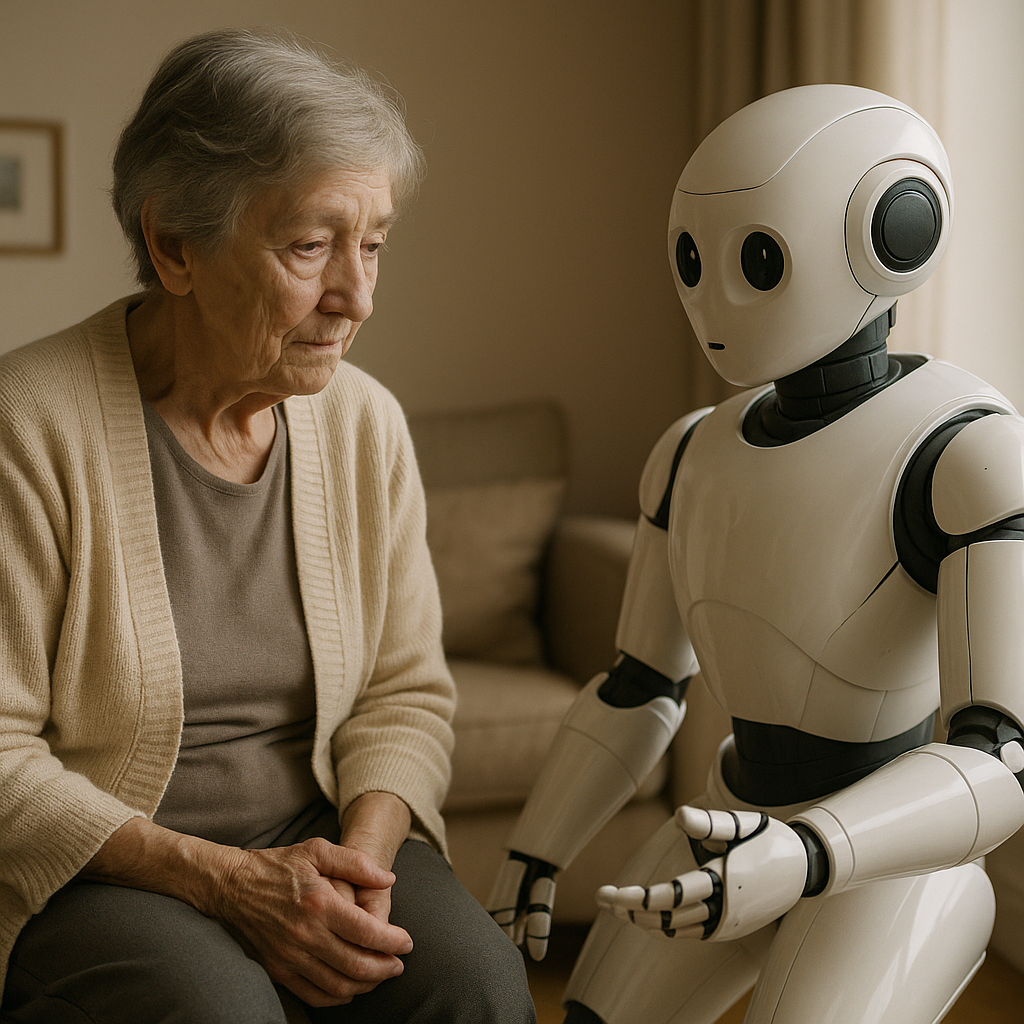

As governments and healthcare systems turn to artificial intelligence to address critical gaps in eldercare and dependent care, a new academic study warns that misplaced trust in social care robots (SCRs) could erode the moral core of caregiving. The study, titled “Trusting the (Un)trustworthy? A New Conceptual Approach to the Ethics of Social Care Robots” and published in AI & Society, challenges the dominant ethical narratives that either blindly endorse or completely reject robot caregivers. Instead, it proposes a new model of “sociotechnical trust” to guide their implementation responsibly.

The authors argue that evaluating SCRs through a binary lens of human versus machine capabilities misses the nuance of care environments, where different types of trust operate simultaneously. By introducing a three-level framework of trust, rational, motivational, and personal, the study offers a detailed roadmap for when and how these robots can be ethically integrated into care systems without compromising human dignity or relational intimacy.

Can robots be trusted to care?

The study dissects trust into three core levels: rational trust, which is based on an entity’s ability to reliably perform a function; motivational trust, which includes expectations of moral integrity and beneficence; and personal or intimate trust, which presupposes empathy, mutual understanding, and emotional authenticity.

According to the research, SCRs can already fulfill the criteria for rational and “thin” motivational trust. For instance, many assistive robots demonstrate high reliability in performing tasks such as delivering medication, monitoring vital signs, or assisting with mobility. Some even incorporate ethical reasoning capabilities that align with narrow caregiving contexts, rendering them trustworthy in a domain-specific sense.

However, the study maintains that current SCRs fall short of enabling personal or intimate trust. Their lack of embodied, intuitive knowledge and emotional reciprocity prevents them from achieving the depth of human care relationships—those rooted in mutual vulnerability, long-term familiarity, and authentic concern for the well-being of the other. While robots can simulate caring behaviors, this simulation cannot substitute for the moral and emotional richness that human caregivers bring.

Despite this limitation, the study insists that the inability to form personal trust with robots does not disqualify them from playing a meaningful role in care environments. Rather, it highlights the importance of aligning the roles assigned to robots with the kind of trust they are capable of supporting.

Does introducing robots erode the ethics of human care?

A common criticism of SCRs is that they risk diminishing the human dimension of care, leading to loneliness, objectification, or even deception—especially among vulnerable populations such as the elderly or cognitively impaired. This criticism often stems from what the authors identify as two misconceptions: first, that only the properties of the robot matter in determining trust, and second, that all care contexts inherently require personal trust.

The authors argue that trust is not monolithic; it is context-sensitive and exists in “zones.” In many caregiving scenarios, such as acute hospital care or routine physical assistance, rational and motivational trust is both adequate and appropriate. The emphasis on personal trust becomes critical mainly in long-term or emotionally intense caregiving relationships. By conflating these varied contexts, critics exaggerate the risks and undervalue the potential benefits of SCRs.

Furthermore, the study reframes the perceived threat of deception not as an inherent flaw of robots, but as a systemic design and communication challenge. Deception arises when users are led to believe that SCRs possess emotional or mental capacities they do not actually have. Avoiding this requires transparent design, user education, and ongoing supervision - responsibilities that lie squarely with developers, healthcare institutions, and policymakers.

What model can ensure ethical implementation of care robots?

To reconcile the practical utility of SCRs with the ethical demands of caregiving, the study introduces the concept of “sociotechnical trust in teams of humans and robots.” Under this model, care environments are viewed as networks of interconnected trust relationships involving robots, human caregivers, supervising professionals, and institutional systems.

This framework envisions SCRs as one node in a broader care ecosystem, where their tasks are carefully matched to the type of trust they can support. For example, a robot might assist a patient with medication reminders (rational trust), while emotional support and personal interaction are handled by human caregivers (personal trust). The system gains moral legitimacy not from replacing humans with machines, but from coordinating their efforts based on an ethically calibrated trust structure.

The model also helps address the problem of responsibility gaps - a frequent concern in AI ethics. By emphasizing the collective accountability of care teams and institutions, the framework ensures that trust placed in robots is not detached from human oversight and moral evaluation.

- READ MORE ON:

- social care robots

- trust in care robots

- ethics of AI caregiving

- robotic caregivers

- AI in eldercare

- trustworthy AI systems

- artificial intelligence in social care

- can we trust robots in healthcare

- AI caregiver ethical concerns

- elderly care with AI

- aging population and AI

- human-robot interaction

- FIRST PUBLISHED IN:

- Devdiscourse