Dangerous bacteria communicate with each other to avoid antibiotics: Study

While suffering from viral fever or bacterial infection, the first thing one does is to take antibiotics. Some bacteria develop resistance to otherwise effective treatment with antibiotics.

- Country:

- United States

While suffering from viral fever or bacterial infection, the first thing one does is to take antibiotics. Some bacteria develop resistance to otherwise effective treatment with antibiotics. Therefore, researchers are trying to develop new types of antibiotics that can fight the bacteria, and at the same time trying to make the current treatment with antibiotics more effective.

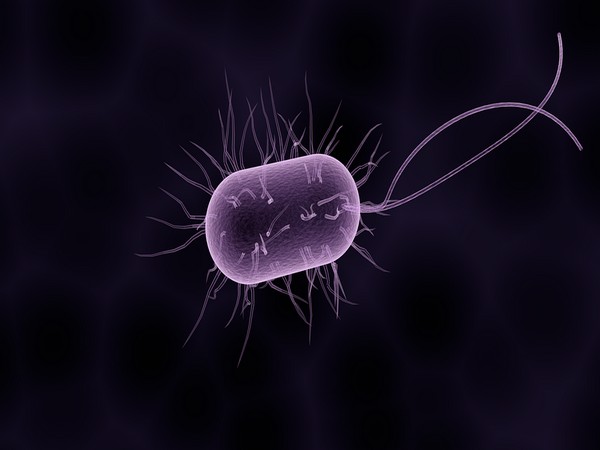

Researchers are now getting closer to this goal with a type of bacteria called Pseudomonas aeruginosa, which is notorious for infecting patients with the lung disease cystic fibrosis. In a new study, researchers have found that the bacteria send out warning signals to their conspecifics when attacked by Scientists reveal antibiotics or the viruses called bacteriophages, which kill bacteria.

The study was published in the Journal of Bacteriology. "We can see in the laboratory that the bacteria simply swim around the 'dangerous areaScientists reveal ' with antibiotics or bacteriophages. When they receive the warning signal from their conspecifics, you can see in the microscope that they are moving in a neat circle around.

It is a smart survival mechanism for the bacteria. If it turns out that the bacteria use the same evasive manoeuvre when infecting humans, it may help explain why some bacterial infections cannot be effectively treated with antibiotics," says researcher Nina Molin Hoyland-Kroghsbo, Assistant Professor at the Department of Veterinary and Animal Sciences and part of the research talent programme UCPH-Forward. One United Organism

In the study, which is a collaboration between the University of Copenhagen and the University of California Irvine, researchers have studied the growth and distribution of bacteria in petri dishes. Here, they have created environments that resemble the surface of the mucous membranes where an infection can occur -- as is the case with the lungs of a person with cystic fibrosis. In this environment, researchers can see both how bacteria usually behave and how they behave when they are affected by antibiotics and bacteriophages.

"It is quite fascinating for us to see how the bacteria communicate and change behaviour in order for the entire bacterial population to survive. You can almost say that they act as one united organism," says Nina Molin Hoyland-Kroghsbo. Possibility of Blocking

The Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteria are such a big problem that they are found in the top category 'critical' in the World Health Organization's list of bacteria, where new types of antibiotics are most urgently needed. Therefore, the researchers are excited to make new discoveries about the ways in which this type of bacteria behaves and survives. "Infections with this type of bacteria are a major problem worldwide with many hospitalisations and deaths. That is why we are really pleased to be able to contribute new knowledge that can potentially be used to fight these bacteria," says Nina Molin Hoyland-Kroghsbo.

However, she emphasises that it will still take a long time for the new knowledge to result in better treatment. The next step is to research how to affect the bacteria's communication and warning signals. "This clears the way for the use of drugs in an attempt to prevent that the warning signal is sent out in the first place. Alternatively, you could design substances that may block the signal from being received by the other bacteria, and this could potentially make treatment with antibiotics or bacteriophage viruses more effective," concludes Nina Molin Hoyland-Kroghsbo. (ANI)

(This story has not been edited by Devdiscourse staff and is auto-generated from a syndicated feed.)

- READ MORE ON:

- World Health Organization