The inclusion imperative: Making Indian economy work for everyone

- Country:

- India

Commenting on the latest round of bank mergers, Finance Secretary Rajiv Kumar said that they were needed to establish the “well capitalized well provisioned banks” that would enable India to join the club of middle-income nations and “support the USD 5 trillion economy.”

The expectation that banks should play their part in enabling a 5 trillion economy is a reasonable one. But, as is widely understood, economic growth needs to be inclusive if it is to contribute to ending poverty. This means that those who are unbanked and underbanked need to be able to participate in and benefit from it. Clearly, a USD 5 trillion economy is of limited value if people are not able to take out agricultural loans, support their children through higher education, and meet other household expenses, without running the risk of debilitating indebtedness. To ease these limitations, banks should play their part in enabling equitable access to public goods (such as a livelihood), as well as those consumable goods and services which can be supported by access to affordable credit.

Financial inclusion, which involves extending financial services to sections of the population hitherto underserved, is a key priority of the Government of India. It is an arena in which the country can demonstrate a number of notable achievements. But it is also an arena that is fraught with challenges. The very process of trying to include hitherto unbanked or underbanked individuals and communities can involve a struggle to overcome not just financial but also other kinds of exclusion, including economic, cultural, and gender-related. The need for collateral to secure various kinds of loans, for example, can serve to exclude those, especially women, who lack ownership of property, from the ability to borrow; while costs, hidden or overt, can also prevent some from being able to access finance.

For those able to borrow, there are various economic risks, both for the customer and for financial institutions. Borrowing can lead to indebtedness; and the practice of charging interest, whether usurious or not, can cause huge problems. The well-documented pandemic of farmers’ suicides shines a harsh light on banks’ fitness for purposes as instruments of truly inclusive growth. Banks need therefore to take steps to protect people from economic risks associated with access to finance. To do this, they should strengthen their financial literacy promotion, whilst being transparent and proactive about terms and conditions and the risks of financial products and services.

They also need to make sure their products work for the poor. As banks look to promote digitization, the financial inclusion imperative demands that they do it in a way that is accessible to the many, not just to the few. As observed by TK Srirang of ICICI Bank at a recent FICCI-IBAC summit, personalization is what customers are expecting, and banks are responding to that. But is enough attention being paid to the needs of financially excluded customers?

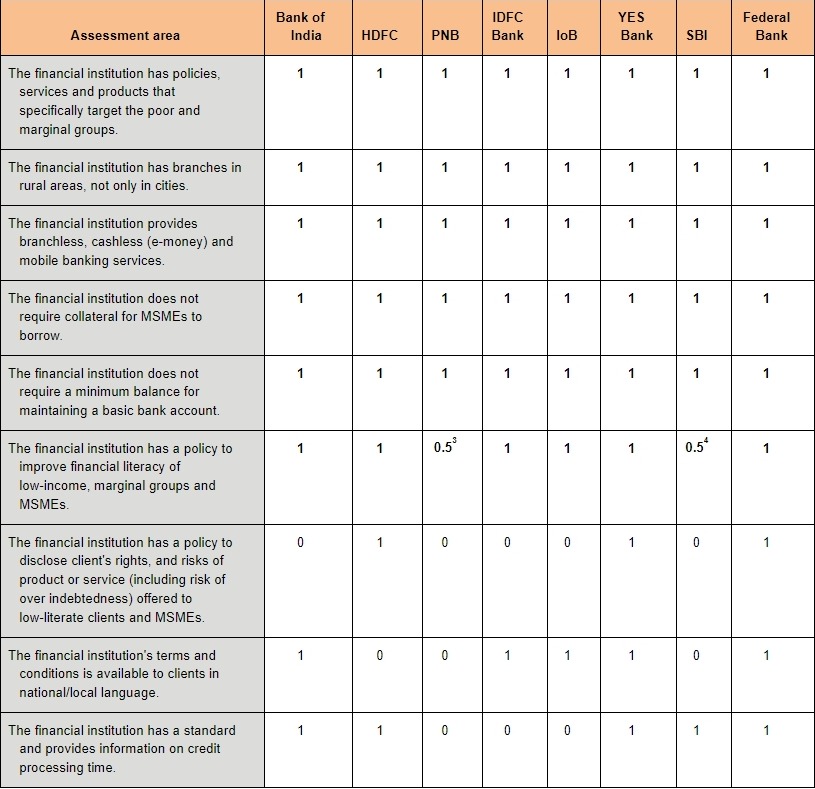

The Fair Finance India coalition, part of a multi-country network on fair finance with presence in Asia, Europe, and South America, has conducted an assessment of policies of 8 major Indian banks. The assessment uses the Fair Finance Guide, which is an internationally developed methodology derived from established responsible business standards. Table 1, below, includes data on policies that 8 sampled banks were found to have on various different financial inclusion parameters.

3 PNB half score due to lack of reference to marginalized groups

4 SBI half score due to lack of a policy

As the table indicates, there is plenty to celebrate in what banks are doing. All banks have set up branches in rural areas and provide branchless, cashless and mobile banking services. None requires a minimum balance for maintaining the basic saving deposit account. While public sector banks like SBI are already well established in these areas, some private banks too, including smaller private banks, have considerably increased their physical presence through an increase in the total number of bank branches, especially in unbanked or underbanked locations.

All eight banks have policies, services or products that specifically target poor and marginalized groups, though there is variance in the level of detail provided regarding particular services available. For instance, Federal Bank offers Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana accounts to the general public (mainly to weaker sections and low-income household groups). All banks have also made a commitment to improving the financial literacy of low-income, marginal groups, and MSMEs.

However, in terms of steps being taken by banks to communicate risks (including risks of indebtedness) associated with financial products or services to low-literate clients and MSMEs, there is a concerning amount of divergence. Only three of the eight banks appear to have a clear policy on this which specifies risks, whilst in five cases a policy presence could not be found. Only five appear committed to providing terms and conditions in national or local languages (i.e. languages other than English).

Data on the Jan Dhan Yojana scheme shows that it has reached staggering numbers, around 20% of accounts were still reportedly dormant as of April 2019. This is illustrative of the need to do much more to ensure excluded groups are able to benefit from the formal financial sector. Additionally, beyond access to finance, there needs to be a renewed focus on ensuring that marginalized populations are made cognizant of the risks involved in taking out loans, ensure products are available in local languages and are also transparent in sharing other information, such as credit processing time.

According to the Ministry of Corporate Affairs’ updated National Guidelines on Responsible Business Conduct (NGBRC), banks should consider their CSR not just in terms of financial literacy programs – though these are clearly important – but also in innovating and investing in “products, technologies, and processes that promote the well-being of all segments of society, including vulnerable and marginalized groups.” (NGBRC Principle 8). Further, banks, like other businesses, should ensure that they minimize and mitigate “any adverse impact of its goods and services on consumers” and “disclose all information accurately… including the risks to the individual” (NGBRC Principle 9). Transparency is a key cross-cutting concern of the NGRBC as for the National Voluntary Guidelines which preceded them.

India is arguably the world’s greatest laboratory for financial inclusion. In a context of rapid change from less formal to more formal economic arrangements, banks have a key role to play as gatekeepers of the formal economy. But for their customers, especially those new to banking, their role does not end there. It is hoped that they leverage their know-how to ensure that the newly banked do not simply access services, but are supported to make good use of them, whilst negotiating attendant risks. In doing so, they will generate lessons not just for India, but for the world at large.

Ileena Roy is a Project Officer, Private Sector Engagement, Oxfam India

Rohan Preece is a Project Manager, Partners in Change

(Disclaimer: The opinions expressed are the personal views of the authors. The facts and opinions appearing in the article do not reflect the views of Devdiscourse and Devdiscourse does not claim any responsibility for the same.)

- READ MORE ON:

- Indian economy

- Oxfam India

- Financial inclusion

- Jan Dhan Yojana

Rohan Preece, Ileena Roy

Rohan Preece, Ileena Roy