Optimizing Healthcare in Africa: Addressing Gaps in Competence and Caseloads

A groundbreaking study by Harvard, Georgetown, and the World Bank reveals that Sub-Saharan Africa’s primary health care crisis stems not from a shortage of providers but from inefficiencies in caseload distribution and underutilization of skilled workers. Addressing these issues through better resource allocation and systemic education reforms could significantly improve care quality.

Researchers from Harvard University, Georgetown University, and the World Bank have provided a groundbreaking analysis of the human resources crisis in Sub-Saharan Africa's primary health care (PHC) systems. Drawing on data from 7,915 health facilities and 14,367 providers across ten countries, the study challenges the narrative that workforce shortages are the primary driver of poor health outcomes. Instead, it identifies systemic inefficiencies in how caseloads are distributed and competent providers are utilized, offering a fresh perspective on the region's PHC challenges.

Uncovering the Paradox of Underutilized Providers

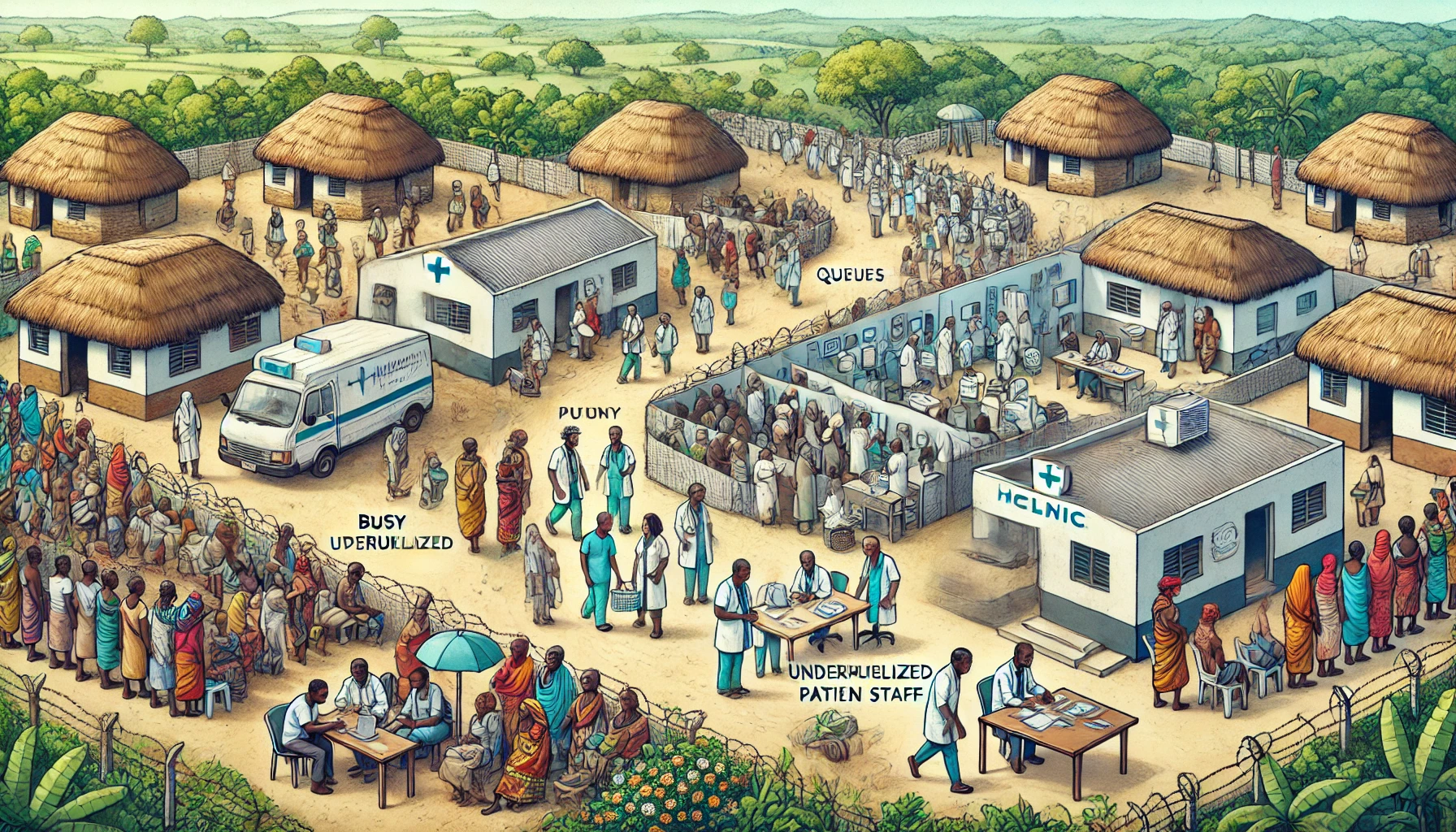

While global discussions often portray Sub-Saharan Africa's health workers as overburdened, this research reveals a different reality. Most PHC providers in the region are far from overwhelmed. The median provider sees only 10.9 patients daily, which amounts to less than two hours of direct patient care. This starkly contrasts with the narrative of severe provider shortages. However, the study also highlights significant disparities: some facilities experience overcrowding, while others remain underutilized. Patients in busy facilities encounter long queues and wait times, shaped by the fact that the median patient interacts with providers handling nearly 25.7 patients per day. This dual reality of underutilization and overcrowding underscores the need for a more nuanced understanding of the workforce crisis.

A Misalignment of Caseloads and Competence

The study's most striking finding is the weak or even negative correlation between caseloads and provider competence. High-competence providers are not being utilized in high-demand areas. In some countries, these providers are seeing fewer patients than their less-competent counterparts. For instance, in Nigeria, some of the most skilled providers serve an average of just 5.2 patients daily. This misallocation means that large patient populations are often managed by less capable health workers, resulting in missed opportunities to improve care quality. This systemic inefficiency poses a significant challenge, as the study demonstrates that competence levels are not aligned with patient needs across the region.

Simulated Solutions Offer Hope

To explore potential improvements, the researchers modeled a redistribution scenario where the most competent providers were reassigned to the busiest facilities. The results were promising: the likelihood of correct management of basic medical cases increased by 4.5 percentage points on average, with some countries, such as Malawi, achieving gains as high as 9.9 percentage points. However, the potential for improvement varied significantly. In countries like Niger and Togo, where both competence levels and caseloads are low, reallocating providers had minimal impact. These findings indicate that while better resource distribution could improve care quality in some contexts, it is not a one-size-fits-all solution.

Beyond Workforce Numbers: A Call for Systemic Reform

The study critiques the dominant narrative of a generalized "human resources crisis," arguing that the problem is not simply a shortage of providers. Instead, it identifies two distinct challenges: inefficient allocation of caseloads and a shortage of highly competent providers in certain countries. For the former, targeted interventions, such as triaging systems and data-driven resource allocation, could yield immediate results. However, for countries with profound shortages of skilled workers, more fundamental changes are needed. The researchers emphasize the importance of overhauling medical education and workforce training systems to address these deeper deficits.

The implications of these findings are profound. The study challenges the assumption that increasing workforce numbers alone will address the region’s health care challenges. Instead, it calls for policies that improve the alignment of provider competence with patient demand. This could involve reallocating providers, enhancing triaging systems, and using real-time data to optimize staffing decisions. Furthermore, the research highlights the importance of directly measuring provider competence, as formal qualifications often fail to reflect clinical capabilities accurately.

In countries with universally low competence levels, the study points to a critical failure in medical education. Addressing this requires more than incremental reforms; it demands a fundamental restructuring of training systems to ensure that providers meet a minimum standard of care. This includes improving education quality, retaining skilled workers, and addressing systemic barriers to professional development.

The research offers a nuanced view of the PHC workforce crisis, emphasizing that the issue is not one of mere scarcity but of inefficiency and inequity in resource distribution. For countries with capable but underutilized providers, reallocating human resources could lead to substantial quality improvements. However, for nations with systemic deficits in competence, addressing the root causes of these gaps will be essential. The findings provide a roadmap for policymakers, emphasizing the need for context-specific solutions tailored to each country's unique challenges.

Ultimately, the study reframes the discourse on Africa’s healthcare workforce, moving beyond simplistic narratives of shortages to uncover deeper systemic issues. By focusing on efficiency, competence, and education reform, the research presents a vision for transforming health systems to deliver higher-quality care to underserved populations.

- READ MORE ON:

- primary health care

- Sub-Saharan Africa's health workers

- PHC

- FIRST PUBLISHED IN:

- Devdiscourse